Just back from an fantastic month in Senegal filming for the BBC Natural History Unit’s Survival series. Our plan was to film chimps digging for water – an amazing behaviour, and one that has never been filmed before.

Just back from an fantastic month in Senegal filming for the BBC Natural History Unit’s Survival series. Our plan was to film chimps digging for water – an amazing behaviour, and one that has never been filmed before.

On arrival it was pretty clear why it hasn’t been filmed before – in fact nobody has even tried filming this population of chimps in the dry season until now. The temperatures you have to deal with, and daily routine required to keep up with the chimps, were extreme and close to the limits of what’s possible.

The amazing Jill Pruetz and her team have been studying this population for 10 years. These are savannah chimps, living in a mixed habitat of desert, scrub and woodland that is very different to the thickly forested areas that we are used to chimps inhabiting. They spend a large proportion of their time on the ground, and exhibit some unique behaviours that allow them to survive in this inhospitable region – digging for water during the dry season being perhaps their most remarkable skill.

Chimps need to drink pretty much daily, and the presence of water defines their range in this part of Africa. At this time of year standing water is rare, and often foul and unpalatable, so these chimps have learned to dig down to the water table. They know the best places to dig – dry river beds – and form patient cues at a good hole waiting in turn for water to percolate into the hole before drinking. Often sticking their entire head into the hole for minutes at a time. Even when there is standing water nearby the chimps will often preferentially dig, and drink from, holes, as the gravel of the stream bed filters the water. Providing cool, clean water as opposed to the scummy, hot, and bee infested surface water.

The daily routine was almost the defining characteristic of the shoot. I’d get up between 3 and 4am in order to drive the 40mins to the study site, we’d then have anything up to an hour’s walk in the dark in order to get to the chimps before they woke up. None of the animals are collared or tagged so the only way of ensuring that you don’t loose them is to stay with them until they have gone to bed at night, then get to them before they wake up and start moving in the morning. Jill is absolutely committed to the welfare of the chimps, and key to this was minimising our impact on them. So only 3 people; Jill, myself, and Michel (Jill’s brilliant research assistant) were allowed in the field on any given day – and often it was just Michel and I. That meant carrying all my own filming kit, plus water and food for the day.

Once the chimps had woken up we’d shadow them all day, trying to spend time with the key characters within the group that we’d decided to feature. They would usually move and feed from 6.30am until around 10am, then rest until 4pm, then another bout of moving and feeding before settling down to nest for the night between 7 and 8pm. We’d then have to walk back to the vehicle – if I was lucky I’d be in bed by 11pm – with an alarm set for 3am the following morning. Although this was typical, the chimps could do anything, and big moves during the day were not unusual; they could move 6km or so when you were with them plus you might have a 4km walk at either end of the day. We quickly figured that you can only do 2 consecutive days in the field and still function, so we settled on a routine of 2 days on, 1 day off.

The heat was brutal; mid 40’sC in the shade, and almost unbearable in the sun. Surfaces were generally too hot to touch, and the camera was painful to pick up. I’d carry (and drink!) 6 litres a day with four sachets of rehydration salts and still feel pretty wrecked by the end of the day. The air was suffocating and like standing in the blast of a hairdryer – added to this was the fact that we wore surgical face masks to prevent possible cross infection – there were times you felt like you were being gently water-boarded. As this was the dry season most trees didn’t have any leaves so shade was hard to find, and typically occupied by chimps, so you’d often just have to slowly melt in the sun.

The chimps themselves were absolutely wonderful, truly fascinating creatures to film and spend time with. With every other species I’ve filmed – from ants to polar bears – no matter how interesting or beautiful they may be, there is always a very clear line between them as ‘animals’ and one’s self. But with chimps that line is blurred to say the least, and you are absolutely certain that you are sharing the environment with a consciousness that is very similar to one’s own. It took a few days for them to get used to me, but by the end of the trip they were plonking themselves within a few meters of me and going to sleep.

To see the chimps in such a harsh and unfamiliar environment was slightly bizarre, I kept thinking of the opening sequence of Stanley Kubrik’s 2001 (one of my all time favourite films) – the similarities were so strong, in my heat addled and sleep deprived state I was half expecting to find the chimps gathered round the Monolith at any moment. The other film reference that came to mind was at bed time when the chimps where making their nests and settling down for the night. A fairly fig-rich diet lead to a cacophony of chimpanzee trouser coughs rivalled only the legendary campfire scene in Mel Brooks Blazing Saddles.

It was a great shoot, and a wonderful team; Emma, Nick, Jill, Michel, Jonny and, of course, the Fongoli chimps, made all the hard work worthwhile, and I think we’ll have a really strong sequence.

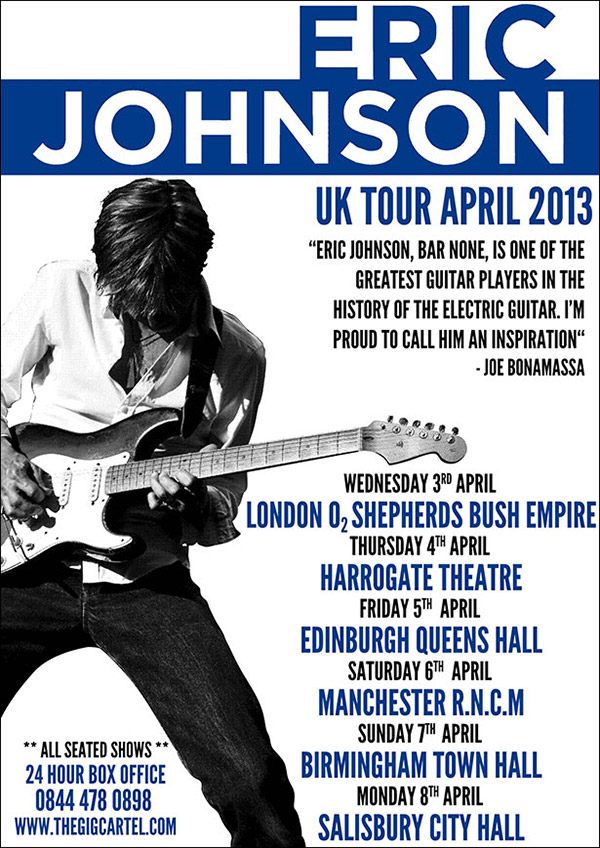

I got back just in time to catch one of my musical heros, Eric Johnson, on the last date of his UK tour – really one of the finest guitarists of the last 50 years – it was a great concert with moments of absolute brilliance – you can’t go too far wrong with a vintage Strat and a loud Marshall stack, I think I’ve lost some of my ability to hear.