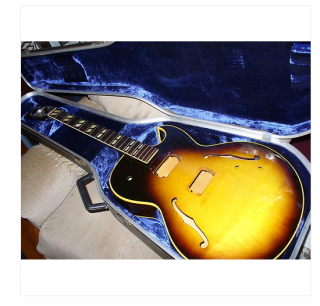

I found this rather forlorn looking Gibson ES175 on E-bay a few months ago. I’ve been really interested in this particular model of guitar for years. It’s the original working professionals jazz guitar, and, as a model, it’s been in production since 1949 – the longest production run of any electric guitar. Originally costing $175.00 (hence the model name), it was a guitar that borrowed design features from more expensive archtop designs in the Gibson catalogue of the time, but with a few refinements that bought its price down within range of working musicians.

I found this rather forlorn looking Gibson ES175 on E-bay a few months ago. I’ve been really interested in this particular model of guitar for years. It’s the original working professionals jazz guitar, and, as a model, it’s been in production since 1949 – the longest production run of any electric guitar. Originally costing $175.00 (hence the model name), it was a guitar that borrowed design features from more expensive archtop designs in the Gibson catalogue of the time, but with a few refinements that bought its price down within range of working musicians.

The most notable design innovation was the use of laminate wood in the front and back of the guitar – a 3-ply sandwich of maple and basswood that was heat pressed to form the distinctive shape of traditional archtop guitars. This was a much cheaper and quicker construction method compared to the usual method of hand carving and tap tuning the front and back plates from solid maple or spruce.

The use of laminate wood, while initially conceived as a cost saving measure, was quickly discovered to have benefits in terms of tone and resistance to feedback while playing amplified at high volume – laminate tops are also less prone to cracking warping due to changes in humidity and temperature.

The ES175 has gone through several incarnations over the last 60 odd years, some good, some not so good. This particular instrument is from 1957 – generally accepted as being the ‘golden age’ of Gibson’s guitar building. Only 273 sunburst finish ES175D (the ‘D’ denoting two pickups) where made in 1957, and it’s unusual to find one in such good structural condition. Many 175’s from this era have had their headstock broken off at some stage in their lives; there is an inherent weakness in the construction of the neck (a solid piece of mahogany). Just under the nut where the wood is rather thin and many guitars from this period have had major surgery to repair and strengthen this area. To find such a clean example was what really got me interested.

It’s sad that someone would have stripped all the hardware and electronics from such a beautiful instrument, but it’s a fairly common practice. The pickups from this era (‘Patent Applied For’, or PAF) are highly desirable and worth a fortune, so dealers ‘part’ guitars like this to sell the pickups individually, or worse, they pop them, into a fake relic Les Paul and try and sell the whole instrument for tens of thousands of dollars. From what I could tell from the photo’s on E-bay it all looked pretty good – no cracks, some lovely checking in the lacquer finish, and the frets, although deeply pitted, looked like they were original and still had some life in them. So I put in a bid and waited.

It all arrived in great shape – even more beautiful than I’d hoped, so now it was a question of restoring the guitar her former glory. My aim was to get this instument back as near as possible to original condition. I knew I’d need to find original examples of some key parts; the bridge – originally carved from Brazilian Rosewood – would not be available as a new replacement part due to that species of tree now being, quite rightly, protected under CITES. The ’57 tailpiece was also a distinctive design, made from nickel, that you couldn’t get an accurate modern reproduction of. So a bit more trawling around on E-bay and I’d found a bridge and tailpiece. The tuners are new reproductions of the traditional Klustons – original Klustons from the 50’s would probably have long since disintegrated.

The electronics would all need to be done from scratch. I contacted Tim Mills at Bare Knuckle pickups, who have made pickups for all my other guitars, and we decided on a set that would suit the character of the instrument. I also sourced vintage spec potentiometers, caps and cloth covered hook-up wire and set to work.

Installing the electronics in an archtop guitar is acknowledged as one of the more challenging manoeuvres known to man – something akin to neurosurgery or James Herriot’s finer moments dealing with breach position livestock. Basically you have to insert a bunch of bulky yet delicate electronics through the existing holes (the pickup and ‘f’ holes) in the guitar’s front then bring them up to the surface of the guitar in the right position to fix them in place.

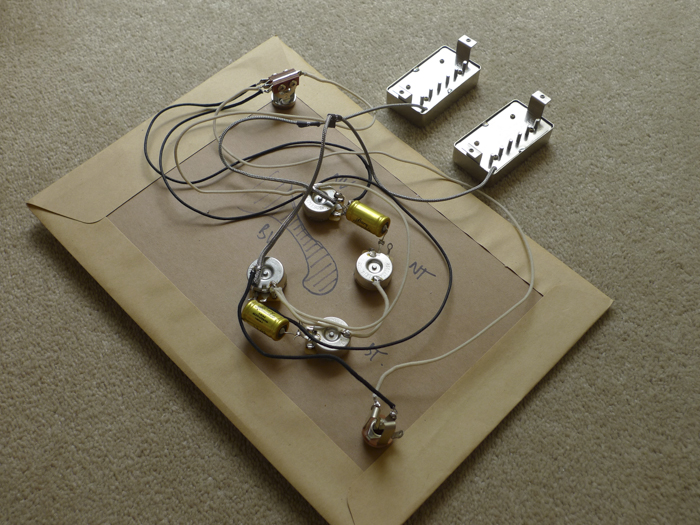

The first move is to make a template of the control layout of the guitar so you can make up the wiring loom. You want to keep things as neat and compact as possible, but at the same time you need to build in enough wriggle room and flexibility to allow you to fit things into place.

Once this is all soldered and tested comes the tricky bit – how do you get all this stuff inside a guitar and fixed in position, when the only access holes you have to work with are too small to squeeze your fingers through.

Surgical tubing is key to success from this point onwards; it’s just the right size to fit over the pot shafts and through the holes drilled in the face of the guitar, so you feed lengths of tubing through the holes in the front of the guitar and push them onto the shafts of the corresponding pot (volume, tone etc). Then you very gently start to ease everything into place – things go wrong, stuff gets twisted, what seems so simple in principle disintegrates into chaos fairly fast, you start again.

Eventually it’s all in place, what worked well for me was the decision to use vintage style hook-up wire which is pretty inflexible and allows the wiring loom to keep its shape as it all gets eased into position. The pickup selector switch is pulled in to position using a length of cotton thread, the output jack using an improvised coat hangar tool. Everything is secured, you plug in … and the neck position tone control doesn’t work. No idea why, you insert a mirror into the guitar, shine a torch and inspect, all looks fine. Everything comes out, test the circuit again, stick it all back in, and it works – it always worries me slightly when things like that happen.

Then it’s ready to string up – always slightly nerve wracking as you don’t know when the last time this guitar was exposed to the 180lb’s or so of pressure associated with being strung with a set of guitar strings tuned to concert pitch. I always imagine making the final half turn of the high E tuning peg and the whole guitar imploding into a mass of splintered carnage. But this all seemed to settle in pretty well – a few creaks and groans, but nothing too alarming.

Despite the fantastic condition that the guitar was in, it had clearly seen some fairly serious action over the years – although its previous owner(s) seemed to know a limited repertoire of chords – as the fret and fingerboard wear was limited to the first few frets. A quick visit to Bob at RP guitars for a fret dress had it playing beautifully.

Despite the fantastic condition that the guitar was in, it had clearly seen some fairly serious action over the years – although its previous owner(s) seemed to know a limited repertoire of chords – as the fret and fingerboard wear was limited to the first few frets. A quick visit to Bob at RP guitars for a fret dress had it playing beautifully.

So now it’s finally all finished. It’s an absolutely beautiful guitar, and a piece of music history fully restored to playing condition. A chunky neck, but not too big, and tone to die for which only comes with age. There is something so special about old instruments, you can be pretty sure they have given multiple people pleasure but you’ll probably never know who owned, played, or listened to them, or what music they played. This guitar was built in Michigan half a century ago, now it’s being played in a little cottage in Oxfordshire – you do wish they could talk.